A Civics Lesson I Never Wish I Needed

On Liberalism, Protest, Radicalization, And White Nationalism in Modern Politics

December 30, 2020

Joseph R. Hunt

Like a lot of people this year, I’ve had plenty of time on my hands with which to devolve into unproductive habits: cruising Reddit for hours on end, often into the early hours of the morning or in bed at night; binge watching Netflix television series – some of which deserved the dedication, some not; reading, reacting to, and becoming unreasonably angry about political headlines on biased news websites; fretting, worrying, and perseverating on global events I have no hand in influencing or changing. I’ve spent a great deal of time delving into new hobbies and revitalizing my interest in old ones.

Like many people, I’ve read headlines from February onwards that threw a pipe bomb into civil discussion within my friend groups and household.

On February 23rd, a 25 year old black man was chased down by men with shotguns in Georgia and murdered – on camera – by three white men for running along a public road in the wrong neighbourhood. It took two months for any legal action to officially be taken by the state of Georgia (all this amounted to, by the way, was the recusal of a prosecutor due to knowing one of the killers and handing over the investigation to the FBI), and this, only after the posting of the recording on the internet.

On March 13th, police entered the apartment of Breonna Taylor and her boyfriend in Louisville, Kentucky during a no-knock raid – searching for Taylor’s ex-boyfriend on drug charges – and were fired upon as intruders. They blindly shot back into the house, killing Breonna while she slept. No search of the house was ultimately conducted, as it was determined that the police had no reason to search the building in the first place; her boyfriend was briefly charged with assaulting an officer with a deadly weapon while defending himself, and a grand jury failed to indict any of the officers involved in her death.

On May 25th, George Floyd was approached by three police officers in Minneapolis, Minnesota on suspicion of using counterfeit bills while buying cigarettes, taken into custody, and eventually prostrated where a white police officer, Derek Chauvin, knelt on his neck for eight minutes, forty-six seconds, choking him to death.

The last year has been bleak, by many standards. Waking up in May and reading about these stories in the news coloured the entire summer for me. Outraged and incensed by yet another series of news stories of violence – police or otherwise – against black Americans, I joined many people in feeling disgust, anger, and bitter disappointment with America. News stories flooded headlines about protests, peaceful or otherwise, throughout the US as thousands of Americans displayed their contempt at the failure of American society and law in addressing the ugly face of our country’s history. In May, I watched Trevor Noah add his own thoughts to the national discussion regarding race, from a video he posted on “the daily social distancing show” on YouTube May 29th:

“… but if you think of being a black person in America… any place where you’re not having a good time, ask yourself this question when you watch these people: what vested interest do they have in maintaining the contract? Why don’t we all loot? … because we’ve agreed on things. There are so many people who don’t have… think about how many people who don’t have say ‘you know what? I’m still going to play by the rules, even though I have nothing because I still wish for the society to exist. And then, some members of that society, namely black American people watch time and time again how the contract that they have signed with society is not being honoured by the society that has forced them to sign it with them…

A lot of people say, what good does this do? What good doesn’t it do? What good does it do to loot target? How does it help you to not loot Target?”

When I first saw Noah’s video, I couldn’t agree more. My secondary reaction was to educate myself and refine my stance on the issue, and try to understand why, in its most extreme sense, my instinctual reaction to these events – and further events surrounding white nationalism and American politics - of the last year have been so heavily influenced by rage, contempt, and a refusal to understand the issues holistically or consider the alternative arguments.

In essence, over the last six months, I’ve been reading, thinking, and trying to come to terms with an emotion I think many of us share this year, as we reel from day after day of headlines which make us ask “what in the ever-loving fuck is wrong with this world?”: that these problems require drastic, unilateral, and sometimes necessarily violent solutions, and that nobody but ourselves are going to provide them.

This stance is reprehensible, intractable, and dangerous; it is also, given enough reinforcement, natural. If you do not traverse the emotional landscape such thinking paints, understand its causes and address the root issue within yourself, it will alienate you from your community, damage your relationships with the people you love, and drive your further into a dark pit in your mind which may ultimately become impossible to drag yourself out of.

Classic Liberalism – A Philosophical Cornerstone

“My purpose is to consider if, in political society, there can be any legitimate and sure principle of government, taking men as they are and laws as they might be.”

~ Jean Jacques Rousseau, The Social Contract

After watching Noah’s video, I almost immediately ordered from Amazon a copy of John Locke’s The First and Second Treatises of Government and Jean-Jacques Rousseau’s The Social Contract. I had seen in two places (the other being Last Week Tonight’s John Oliver) an argument addressing social contract theory – a political theory in which individuals exiting the state of nature and entering into social life agree to written and unwritten agreements on fundamental rules, regulations, and norms in order to advance their own interests and the common interest of all participants. Many writers, from the 18th century on, have weighed in on the topic, and an exhaustive list of the dialogue here is impossible. For my own interests, I was curious to know what, exactly, the social contract is, how it comes about, and what consequences it has for society when it fails to serve the common good of the people.

Rousseau – The Social Contract

Rousseau writes that the social contract is, first and foremost, is an abrogation of man’s rights in the state of nature: man in the state of nature has only one interest, that of his own (and his children’s) survival and the provision thereof. In this state, man is war-like, territorial, and possessive, but also innocent: the notion of “the noble savage”, while fraught with perilous racial undertones in history, is something like man as Rousseau describes him. The conflict of one individual with another, he defines as the state of war – a state in which man does not enter unless in defense of property, necessary for the survival of the individual or the individual’s familiars. In this state, man is ignorant of both liberty and their own faculties. When concerned only with survival (something Maslow would certainly attest to), no higher principals may exist. It is, however, a natural and perhaps inevitable shift that men, eventually, recognize the need for harmony among competitors, and civil law is a natural consequence. Like children in relation to fathers, the surrender of individual, natural freedom is advantageous and serves our goals better than natural struggle, so we sacrifice our natural rights for those accepted in society. In particular on the topic of inequality, the submission to civil law “substitutes.. a moral and lawful equality for whatever physical inequality that nature may have imposed on mankind…”.

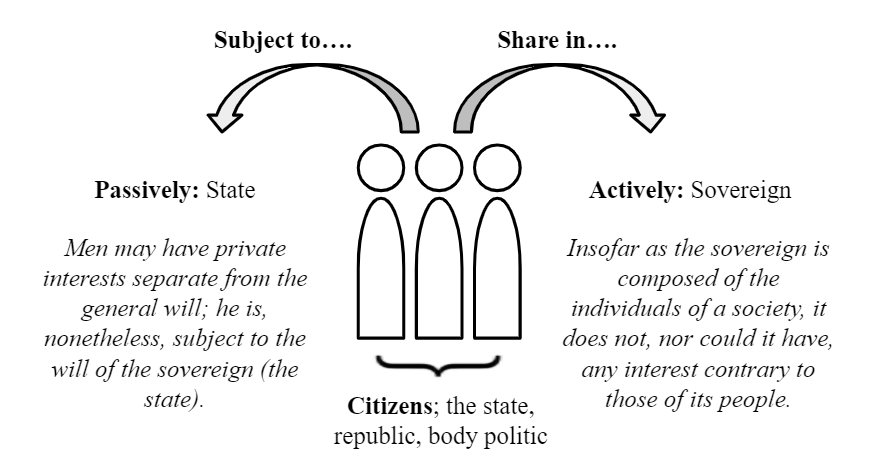

In return for the loss of natural rights, men gain civil rights; they reserve the right to found, upon right of the sovereign, law that rules and dictates the organization and function of society in order to serve their needs. Particularly, the social contract is the natural answer and solution to the necessity of preserving each man’s own strength and natural liberty, which are the means of his preservation, without imperiling himself. As each man gives himself to the common, he therefore gives himself to no one man. Likewise, there is no one whom does not now have the same rights as him. Men are responsible for remaining active members of this society, as the only true and valid right to rule remains, ultimately, with the people. In fact, he writes “a people is a people even before the gift to the king is made. The gift itself is a civil act; it presupposed public deliberation”.

Figure 1: The People and the Sovereign

Of interest in book 1 is Rousseau’s rebuttal to the notion of “might making right”: he writes about early notions of mankind in nature in Hobbesian terms (“men akin to cattle”), and to Aristotle’s claim that men are created inequitably, with some born to slavery and others to become masters. Even so, no slavery has ever been natural, as no man has a right to divest himself of his liberty; such divestment is by force, and perpetuated, at worst by slaves, by their own cowardice and failure of duty towards themselves. The natural consequence, then, is that yielding to force is an action of prudence, the “...strongest man is never strong enough to be master all the time, unless he transforms force into right and obedience into duty”. As soon as force is no longer able to be utilized, all pretext to duty by the enforced is void, and one is no longer responsible for obedience. By a similar argument, Rousseau declares that – apart from the state of nature – war is an act between states, and that a just state (or the prince, the state’s executor) cannot justifiably lay claim to the property, liberty, or lives of a state’s people within or without the state of war.

Of the organization of such a people, Rousseau writes of sovereignty that it is indivisible and restricted only to the general will of a people. After all, it is only in the common interests of all involved that natural liberty is sacrificed; the laws of a state, insofar as they serve the general will, reconcile a particular with it. Laws generated in this way represent political laws by definition, and fall into three categories: civil, criminal, and moral law. These laws exist as acts of the sovereign used to address concerns of particular interests and conflicts, as the general will, by definition, cannot engage in particular issues. And insofar that individuals have agreed to form a society, they are subject to these laws – even if their particular interests tell them otherwise – as their own association with society is participation in the general will and therefore the particular will of law. An individual’s act against the general will or the law (for example, the refusal of participation with the social pact) is itself an act of war, and such an individual is subject to punishment. Note, however, that the individual is to be punished only insofar as it is necessary to restore him to the general will; he ought to be “forced to be free”.

From the deliberations of a well informed people, Rousseau writes the will of all (private, individual wants) can be compared with the general will (the best interest of the people) and the result is what should drive political law. It is important, however, that no “sectional associations” or factions be allowed to exist – or, at least, that they be as numerous as possible to prevail against inequality.

In a similar vein, Rousseau doesn’t fail to address the issue of executive versus legislative power: to the latter, he assigns the duty of the people – as the only legitimate government, the sovereign – to enact fundamental, political law; to the former, he assigns the execution of such law. Executive power, by definition, “cannot belong to the generality of the people as legislative or sovereign, since executive power is exercised only in particular acts … outside the province of law”. A state necessarily needs a government, which serves as this intermediary body – and often confused with the sovereign – to maintain civil and political freedom. Members of the government are termed magistrates, who use the public force of the sovereign to enforce obedience to their general will. Rousseau notes that government itself has its private interests (self preservation, as perhaps its largest), but that it must remain committed to the duty of sacrificing itself to the people. Signs of a good government include the increase and provision for growing citizens is perhaps the easiest definition; moral considerations are difficult, particularly as not all governments are suited to all peoples.

Inevitably, it is important to note that government can and does exert itself against the sovereign will, and at some point begins to act against the social contract. Insofar as the government does so, the people are no longer subject to rule of the government, as the sovereign itself dissolves and the people are subject by force to obedience. Such a state is anarchic in nature. Rousseau, taking men as they are, makes due note that it is impossible to guarantee a lasting and eternal constitution: only through the legislative power of the sovereign is the state able to endure, and it is instead better to allow for the dissolution of the government in order to continue serving the general will – which laws, as acts of the general will, may sometimes be found lacking or contrary. Rousseau, quite cogently, reminds us that the sovereign only acts to further the general will; it does not, necessarily, always know what that general will is. “the moment the people is lawfully assembled as a sovereign body all jurisdiction of the sovereign ceases; the executive power is suspended, and the person of the humblest citizen is as sacred and inviolable as that of the highest magistrate”.

John Locke – The State of War, Actions against the Government

“Whosoever uses force without right, as every one does in society, who does it without law, puts himself into a state of war with those against whom he so uses it; and in that state all former ties are canceled, all other rights cease, and every one has a right to defend himself, and to resist the aggressor”.

John Locke, Two Treatises of Government

On the state of war, John Locke defines it as “a sedate settled design upon another man’s life” which exposes his life or property to the other’s power; within the state of war, the fate of the innocent man is to be preserved above all else, and an aggressor in such a state has forfeited all right to life or property. It is also natural to deduce that aggressors in a state of war have no other intent than absolute power over an individual, and must be supposed to have a design to take away everything from a man if he has an intention of limiting his freedom. In this state, there exists no common superior to appeal to for remediation/arbitration. Quite naturally, men want a common mediator; without the presence of any authoritative source for justice or peace, though, this state perseveres indefinitely, and is perhaps the first reason for an agreement between men to renounce natural liberty for those of civil life. Since this need for freedom from absolute and arbitrary power – a natural right – is so imminently necessary for social life to exist, no legitimate state may exercise a right over another’s life: “This is the perfect condition of slavery, which is nothing else, but the state of war continued, between a lawful conqueror and a captive… no man can, by agreement, pass over to another that which he hath not in himself, a power over his own life”.

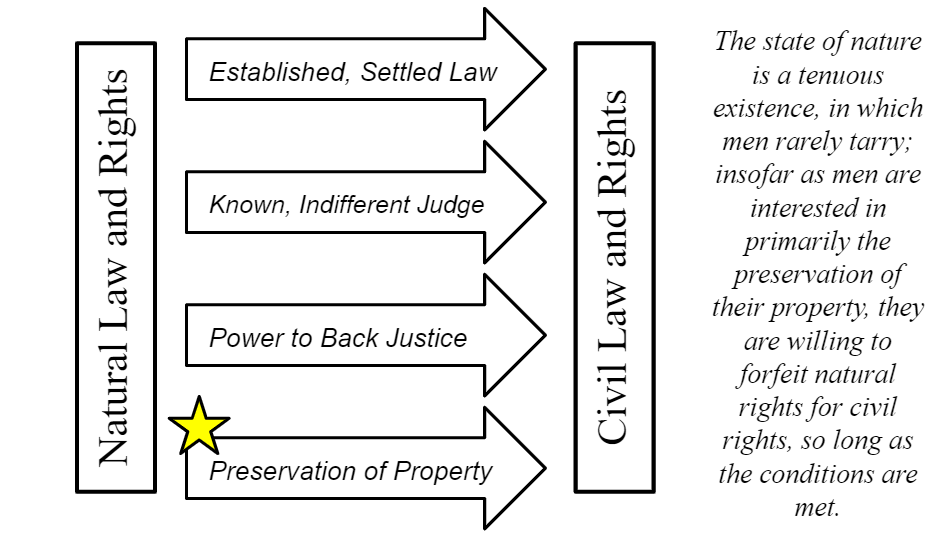

Figure 2: desires in the state of nature, pushing to civil law

Of the opposition of the prince (Rousseau’s magistrate; the executive power): the power of the prince may be opposed insofar as “force is opposed to nothing, but to unjust and unlawful force; whoever makes an opposition an any other case, draws on himself a just condemnation both from God and man”. Given that the executive is invested with the right to execute the law as written by the people, it is counter-productive to claim that the people may counteract their own interest. However, if the unlawful acts by the magistrate persist and have no remedy in law or be obstructed, men as a polity may resist only insofar as its in the general will of the people; even organized groups of men acting against unlawful actions by the government, may not themselves engage in actions disturb the legitimate rule of the people, lest they dissolve the society. Locke is quick to note, though, that if the unlawful action act against the majority of the people or if the consequences of the government against a few offend all involved, there is no case he can envision in which he can reasonably say the people are obliged to maintain their society or the government. He states later that it must be a careful decision whether to dissolve government or society, and that the dissolution of the people is either an act of a foreign power or an act of the government to 1) set up as arbitrary their own will against the people, 2) the prevention by the government of the lawful assembly of the people and acting freely for the general will, or 3) the elections or process of election by the people are altered without their consent.

“… such revolutions happen not upon every little mismanagement in public affairs. Great mistakes in the ruling part, many wrong in and inconvenient laws, and all the slips of human frailty, will be born by the people without mutiny or murmur. But if a long train of abuses, prevarications and artifices, all tending the same way, make the design visible to the people, and they cannot but feel what they lie under, and see whither they are going; it is not to be wondered, that they should then rouze themselves, and endeavour to put the rule into such hands which may secure to them the ends for which government was at first erected”.

A Brief History of Iniquity

“You deplore the demonstrations taking place in Birmingham. But your statement, I am sorry to say, fails to express a similar concern for the conditions that brought about the demonstrations. I am sure that none of you would want to rest content with the superficial kind of social analysis that deals merely with effects and does not grapple with underlying causes. It is unfortunate that demonstrations are taking place in Birmingham, but it is even more unfortunate that the city's white power structure left the Negro community with no alternative.

In any nonviolent campaign there are four basic steps: collection of the facts to determine whether injustices exist; negotiation; self purification; and direct action. We have gone through all these steps in Birmingham. There can be no gainsaying the fact that racial injustice engulfs this community. Birmingham is probably the most thoroughly segregated city in the United States. Its ugly record of brutality is widely known. Negroes have experienced grossly unjust treatment in the courts. There have been more unsolved bombings of Negro homes and churches in Birmingham than in any other city in the nation. These are the hard, brutal facts of the case. On the basis of these conditions, Negro leaders sought to negotiate with the city fathers. But the latter consistently refused to engage in good faith negotiation…

...You may well ask: "Why direct action? Why sit ins, marches and so forth? Isn't negotiation a better path?" You are quite right in calling for negotiation. Indeed, this is the very purpose of direct action. Nonviolent direct action seeks to create such a crisis and foster such a tension that a community which has constantly refused to negotiate is forced to confront the issue. It seeks so to dramatize the issue that it can no longer be ignored. My citing the creation of tension as part of the work of the nonviolent resister may sound rather shocking. But I must confess that I am not afraid of the word "tension." I have earnestly opposed violent tension, but there is a type of constructive, nonviolent tension which is necessary for growth. Just as Socrates felt that it was necessary to create a tension in the mind so that individuals could rise from the bondage of myths and half truths to the unfettered realm of creative analysis and objective appraisal, so must we see the need for nonviolent gadflies to create the kind of tension in society that will help men rise from the dark depths of prejudice and racism to the majestic heights of understanding and brotherhood. The purpose of our direct action program is to create a situation so crisis packed that it will inevitably open the door to negotiation. I therefore concur with you in your call for negotiation. Too long has our beloved Southland been bogged down in a tragic effort to live in monologue rather than dialogue.”

Martin Luther King, Jr. - Letter from a Birmingham Jail, April 1963

The impetus for this essay was Trevor Noah’s rhetorical question: why shouldn’t black people loot? Before fully involving ourselves in the response to the question, I think it’s critical to fully understand the history behind and justification for such a statement.

American history – even that not so far in the past – records a plurality of instances in which equal protection under the law for black Americans has no guarantee. It wasn’t until the American Civil War (1861-1865) that the topic of slavery was addressed in America, and even here, a pragmatic reading of American history will highlight concerns outside of whether slavery itself was a moral abherration: significant issues at the time surrounding state power, representation, and the expansion of anti- or pro-slavery politics in the American west. Up until the war broke out, bitter debate among lawmakers ran rampant regarding the constitutionality of establishing slave states, often driven by a fear of decreasing northern influence in government.

Even after the bloodiest American conflict in history, the United States would have to endure another century of political and sometime literal conflict surrounding the transition for black Americans from slaves to freed men and women. Following the Civil War, southern states were hothouses for vehemently partisan political initiates targeted at limiting the political rights and powers of not only black Americans, but also of Republican politicians who were involved in lawmaking. Reconstruction in the south ultimately suffocated, driven out by Democratic resurgence in politics, and the implementation of the infamous Jim Crow laws, policies designed specifically to limit/restrict black American votes and political influence through the use of poll taxes, literacy tests, or outright disenfranchisement. Campaigns driven at the local and state level were often supplemented by violent actions by white supremacist organizations. Black Americans suffered for decades under a system of segregation, which divorced them from the rights given to them after the war and were legitimized under Plessy v. Ferguson (1896).

Not until the 1950’s would the constitutionality of such racist segregation laws come under attack. With the supreme court ruling in Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (1954), the doors were opened for serious action to be taken by state/federal governments to begin dismantling and tearing down Jim Crow era laws and to properly reinforce the rights of black Americans in society. Within a decade, massive movements led by Black leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. (who was monitored closely by the FBI and assassinated in 1968), the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, the National Association for the Advancement of Coloured People, Rosa Parks, and – yes – Malcolm X (assassinated in 1965) had entered the public consciousness. Massive protests, demonstrations, and marches occurred during the civil rights movement that drew a clear and uncomfortable picture of the inequities present within American society. Widely televised police beatings and attacks on peaceful demonstrations galvanized action by Americans, and the civil rights movement, already becoming a juggernaut in and of itself, was joined by many white Americans ready to set a new precedent in America. The American government, feeling the pressure, signed the Civil Rights Act of 1964 which forbade discrimination on sex, race, colour, religion, or creed; following shortly after, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 outlawed the use by states of segregationist poll taxes, literacy tests, or other countermeasures in limiting the vote of black Americans. The passage of these laws was, to put it lightly, a contentious topic: numerous instances of federal involvement in state politics and affairs can be found in regards to the events of desegregation in our country, with varying degrees of success. Even now, fifty years past the passage of these laws, evidence can be found of the revenant of segregation playing a hand against the enforcement of the self-evident truth that yes, indeed, all men and women are created equal.

What follows are topics not reliably taught in American history textbooks, especially for children. Perhaps due to proximity, or perhaps to still smouldering ideological differences, we see a continuation of violence against and by black Americans; in 1968, Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated, sparking nation-wide riots and protests which led to significant destruction in numerous American cities; following criticism of the methods of peaceful protest, the 1970’s saw the rise in power by the Black Panther Party, which advocated for social change and the empowerment of black Americans. While ultimately a response to the violence and disenfranchisement of black Americans, the party engaged in retaliatory assassinations against police officers throughout the ‘70’s, and was the subject of multiple internecine, conflicts which led to the split in and decline of their influence in American politics. In 1992, widespread riots in Los Angeles, California, occurred injuring thousands after four police officers were acquitted of charges in the brutal beating of Rodney King, a black man during an arrest.

In more modern history, the murder of Trayvon Martin and acquital of his killer, George Zimmerman, in 2012 became a catalyst for the formation of the Black Lives Matter organization, which advocates for peaceful and non-violent protest against police brutality against black Americans.

A Statement on Violent Protest

I’ll be the last person to tell you that this is either an exhaustive or fully nuanced and accurate analysis of American history. My area of expertise has never encompassed the analysis of primary source documents, thorough and meticulous searches of national or library archives, or first-hand accounts from people with direct experience of the issues surrounding racism, police violence, or inequality in our country.

The truth is this: I’m an average American, with a little too much time on his hands, and a reliably quick internet connection.

Even so, there’s a certain appalling characteristic, a dark je ne sais quoi I feel at even a cursory foray into the history of my country: it doesn’t take much effort at all to unearth a troubling and disturbing list of dates, events, names, and ideas surrounding a longstanding tradition of violence against black Americans. For the last year, as I’ve taken an increasingly closer look at things, I’ve struggled with the revulsion I feel at the state of society; I can’t but help think to myself, after listening to reports of violent protests (which, by the way, make up less than 7% of the 7,750 demonstrations across the country) and watching police gas, beat, and shoot at demonstrators for a better equality among American citizens: at what point are these people going to become fed up and start shooting back?

This is far from an unprecedented phenomenon: American history has, at its basis, the violent rebellion as a nation against the British as one of it’s mythological cornerstones, in which Americans firing upon British soldiers, the marginalization and punishment of loyalists, and engagment in open war for sovereignty on the international stage is the summit of American patriotism and self-sacrifice. Even among some Americans viewing the Civil War as a response to and rebellion against the increasingly large federal powers of the government and the defense of state’s rights, the killing of Americans was seen as a necessary evil to defend a way of life founded on slavery.

It’s only when the topic shifts to the right of black Americans – and, perhaps, the other Americans willing to support them – to protest, violently, if necessary, the infringement and disproportionate violence against them that the discourse turns to one of “rioting”.

It’s an argument with a strong basis. From the onset of our nation’s history, an entire class of people have been repeatedly and forcefully written off into the margins; widespread and effective stratagems have been employed on a legal or para-legal level to ensure that, even up until recently, every measure was taken to ensure that black American rights came second to those of others. It is a well-documented truth that, at the height of the civil rights movement, the American government was deeply interested in monitoring, tracking, and countermeasuring the actions of advocates for civil rights: COINTELPRO, a notorious FBI program responsible for the monitoring, harassment, and intimidation of Americans, is but one example. The expansion of the rights and freedoms of many Americans has been the explicit interest of many organizations throughout the country temporally and spatially. When an eye is turned to the outcomes and results of peaceful demonstrations, like those engaged in by the late representative John Lewis, its an exercise in noting a frustratingly slow, gradual acceptance of facts that ought to be patently obvious to everyone in acceptance with our national creed. It is no surprise that followers of Malcolm X, as just one example, set a precedent for violent protest – if necessary – to defend the rights of American citizens in a country covertly and overtly hostile to their exercise that was followed by other organizations, like the Black Panthers, which acted against the tenets of societal life.

It’s here that, despite the siren call, we must advocate against the external argument of action against the system and, necessarily for, that within if we wish to stand any fair chance against the dissolution of our nation.

In previous pages, I outlined some basic tenets laid down by John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau.

A fundamental basis is that of the argument against the right of rule by force: Locke and Rousseau both beautifully and unequivocally assert that no truly righteous or legitimate right of government by man can be founded upon the threat of force. It follows naturally that, as Locke would have argued elsewhere, that nowhere else finding a legitimate claim that one man has some divine or paternal right to sovereignty over another (despite some claims by modern and not-so-modern demagogues), that it is a grotesque and inconceivable event that a man can claim dominance or superiority over another through slavery. A man in submission is bound by no true obedience to a man threatening him: a man in fear may justify, pragmatically, that a state of servitude is better than a state of death, but upon the end of the threat of force, he is, most fundamentally, obligated to liberate himself. Man is created free; in the state of nature, he is primarily concerned with the defense of self and of property, which is defined as his rightful possession as the product of labour from the natural world around him. The only threat upon him is the threat upon his life or property, and at the end of such a threat, he is not obligated, under any argument, to obey another.

Here we find a justification so basic, so obvious, that it’s enshrined in the Declaration of Independence:

“The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen united States of America, When in the Course of human events, it becomes necessary for one people to dissolve the political bands which have connected them with another, and to assume among the powers of the earth, the separate and equal station to which the Laws of Nature and of Nature's God entitle them, a decent respect to the opinions of mankind requires that they should declare the causes which impel them to the separation.

We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness.--That to secure these rights, Governments are instituted among Men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed, --That whenever any Form of Government becomes destructive of these ends, it is the Right of the People to alter or to abolish it, and to institute new Government, laying its foundation on such principles and organizing its powers in such form, as to them shall seem most likely to effect their Safety and Happiness…”

Going further: men in the state of nature are in want of four crucial needs, which cannot be sated naturally. In the state of nature (which, I’d argue, can be interpreted rather closely perhaps with the state of anarchy) men have no recourse to wrongs, and are only rightfully entitled to the righteous correction by force of an infringement on their rights by the power they possess within themselves. This is deeply problematic: Rousseau and Locke both agree that such a state is brutish, vile, and incorrigibly destructive without end. A system in which men are at war devolves into an interminable squabble of injured parties, laying waste to one another indefinitely without end – how can there be? Thus, a natural transition in which the sacrifice of natural rights are transmuted into civil rights among a polity is a consequence of the failings of natural law; men are willing to reduce their natural, personal rights for the stability of and mutual defense of basic, fundamental tenets shared in common by a body with the power to execute the consequences prescribed by law.

A notable characteristic, which many attribute to social contract theory, is the fact that one mustn’t necessarily explicitly agree to (literally or ceremoniously) abrogate their natural rights: the simple participation in social relationships, enjoyment of its product, or reliance on and benefit from its law require one to become subject. This is the heart of my first diagram, in which I illustrate Rousseau’s description of the sovereign.

This is a contentious point. One mustn’t necessarily agree to the contract to be subject to it; as a result, it is therefore unlawful to attempt to justify the participation in violent insurrection or protest against the society founded by the people. Criticism of the Black Lives Matter movement, ANTIFA, and the protests across the nation focus on the destruction of local property, public spaces, and even installations of artwork (see: the defacement of a statue commemorating the Armenian Genocide here in Denver), not to mention the instances of harm inflicted on police. In this, criticism of the movement is well founded: as people attempting to defend and draw attention to a perceived or real deficits in their rights, they are, necessarily, defining themselves as both subject and non-subject to the rule of the people. By claiming that society is unjust, they are removing themselves from its rule, and thus the rule of law – while simultaneously advocating for their inclusion within it! This is absurd. Either one is or is not subject, and the declaration of non-subjection is a rather terrifying claim to make. The state of nature is a violent, disgusting, and bleak existence, and will initiate a horrifying chain of events within civil society that could be the vanguard of dissolutions with unintentional and far-ranging effects. Advocates for violent rebellion would do well to keep this in mind.

Even further: Rousseau and Locke both do well to state an unfortunate, inevitable fact: men are human. Rousseau, writing as he does, decides to take men “as they are”, in full recognizance of our shortcomings and failures: he outlines the sketch of just government by the people, while occasionally peppering his work with the recognition and description of the limits of man. It is inevitable that, at some time, dissolution of government becomes necessary as the prince or magistrate – the legitimate role of the executive in government, established by the people – becomes corrupt, self-interested, and self-serving. Human history is dotted with failed republics, democracies, empires, and kingdoms; Rousseau, and even Locke, didn’t have far to go to draw a faithful rendition of the conditions in which these governments grow. As such, both authors had much to say about the dissolution of government, especially in legitimate ways as the legislative/sovereign/people reclaim power and institute for themselves a new government (this too, found in the Declaration of Independence).

In the same vein, an interesting counter-argument for the illegitimacy of violent protest is this: violent protest, at times (and supported by our quoted authors) necessary for the defense of the people, can be legitimate in reaction to a corrupt government/magistrate. Such is the argument of many organizations throughout American history: the American patriots of the 18th century, the confederates of the 19th; and many reactionary groups, both black and white, in the 19th and 20th. It could, perhaps, be argued that movements by groups such as the Black Panther Party, Black Lives Matter, or even the Nation of Islam are reactions to corrupt government no longer acting in the interest of the general will of the people: to this, I respond, that it is the most dangerous and nuclear of options.

A proper government, elected and legitimized by the general will, has as its interest no other than the defense and preservation of the civil rights of everyone; to this end, a just government executes no law or action in contrary. It is in ideal argument, surely – many counterexamples, even only in American history, could be leveled here – but it is crucially important to note just how general this general will is: it can only be defined as the best interest of every single member of a society, and is comprised of only the most basic assurances and rights. This is a serious challenge for deeply democratic societies as large as the United States, whose members are as diverse as all the nations of the world. I sympathize with and believe in the argument that there are serious and systematic problems within American society, but to claim that a government is illegitimate – even on such a well-justified claim that black Americans are systematically marginalized – has dire ramifications indeed for all people. I see no faster path to total anarchy – and, naturally, the abrogation of any rights by Americans, black or otherwise – than to claim the society we have so carefully constructed and defended for the last 245 years is illegitimate. There can be no other consequence here than of massive and swift intervention by the government, justly used in the defense of the common interest of the sovereign.

Here, we come at last: the use of violent protest, no matter how well founded or justified, cannot reasonably be used to justify any movement whatsoever by any group acting outside the interest of the sovereign will. By membership in a society, we are obligated and subject to the defense of the interest of not only the highest member, but also the lowest. I share in the outrage, anger, and bitter disappointment felt by many Americans when I watch a white police officer choke a black man to death on a street. This is unconscionable – equally unconscionable, though, is the reversion to an outright state of war against America itself. To seek recourse in the law by acting outside it is absurd, and warrants an immediate reaction to stamp out violent opposition.

In this, I take a great deal of solace from the life and work of peaceful protestors like Martin Luther King, Jr., and the many thousands of Americans engaged in the peaceful protest of police brutality against black Americans this year. On the basis of what our nation is founded on, I see no other current example in bravery or citizenship. Though frustratingly, heartbreakingly slow, the movements inspired by black organizers and their supporters in the south during the 1960’s is an inspiring paragon not only for the example of all American citizens, but also for the truest exercise of the higher faculty of mankind.

The Reverse of the Coin: White Nationalism and Alt-Right Populism

Perhaps one of the most disturbing trends in American politics I’ve seen in the last ten years: the rise of populist, alt-right ideology in the United States. This is an emergent problem in politics and social life across the globe. Like many people, I was shocked when I read about the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally, in which neo-nazis, white nationalists/supremacists, and Trump-supporting conservatives gathered wearing white polo shirts and store-bought tiki torches – looking much akin to a frat party on a panty raid – gathered in Virginia in 2017 to protest the removal of Confederate general Robert E. Lee’s statue in Lee Park. The event sparked widespread outrage across the US, generated hours of cable news coverage, and drew sharp focus on the alt-right when one of the white nationalists at the rally ran over twenty people, killing one of them.

Like many people, I found it horrifying to read and see the footage of the events, especially in a country in which we elected (and re-elected) our first black president in 2008 and 2012.

It must be noted, however, that the issues surrounding the alt-right movement now (demographic change, stagnation of working-class society, political representation, gender roles/rights, and cultural conflict) are neither novel nor particularly revolutionary problems: American history is littered with overtly racist beliefs and events, arguing a bad-faith conservation of the dominance of particular groups over another. Many issues surrounding race in this country are recent history, if ever buried in time, and the recent toxification of the political arena and the unofficial efforts by many groups to re-legitimize racist and white supremacist rhetoric in the political arena must be addressed directly.

Samantha Kutner of the International Center on Counter-Terrorism is one of a growing number of academic scholars taking a closer look at the issue of white nationalism. Kutner, an alumna of the University of Nevada, Reno, published a journal article titled Swiping Right: The Allure of Hyper Masculinity and Cryptofascism for Men Who Join the Proud Boys in 2020 as an effort to bring a greater focus on the push and pull factors present among young white men that drive them into such extremist ideology. In a rather interesting study, Kutner conducted interviews with 17 members of the Proud Boys, ranging from new initiates to inveterates via Twitter, encrypted apps, or telephone interviews. In an attempt to accurately portray the views and history of the group, she paints a portrait of the typical member: a young, white, Conservative man excluded from society on the basis of shifting demographic or cultural beliefs away from traditional values, who view themselves as victims in a precarious position of defending white, western culture and history against what they claim is white genocide. Oftentimes, members commiserate about the “effeminate” state of society, which they believe requires hyper-masculine reactions in order to combat a growing feminist movement in American society. Utilizing unofficial, loosely decentralized platforms for communication, and marshaled by the (apparently) persuasive and charismatic Gavin McInnes, members communicate largely through memes and internet message boards, where they collectively air grievances in their “safe spaces” regarding their predicament of being “too socially liberal for conservatives, too conservative in many political views for liberals” – or, as Kutner ironically points out, their lack of social skills, in particular with their ability in dating/forming lasting relationships with women.

Kutner records a general appreciation for the edginess and rebellious nature of the movement among supporters, who ultimately bond with one another and enjoy the sense of “brotherhood” and cameraderie that so many of them have felt deprived of for most of their lives. In defense of this newfound membership of their community, members often become apologists for the more extreme views espoused by their members and their leader McGinnes, citing the perceived necessity of self-defense in the face of a growing leftist influence at colleges and universities. It is not surprising, here, to learn that the last task in becoming a fourth-degree member requires the use of violence against a group the Proud Boys have aligned themselves against.

White nationalist violence is not an irregular event: even a cursory search of the last decade will produce a terrifying array of mass violence, often enacted by a lone actor, and inspired by literature produced and disseminated by known hate groups. Pulled from the Southern Poverty Law Center, below are only a few vignettes in American infamy one can find with little to no effort.

American white nationalism, undoubtedly older than described here, can be traced back to militias and extremo-conservative, libertarian ideologies from the 1990’s, especially in light of the events of Ruby Ridge, Waco, or the Oklahoma City bombing perpetrated by Timothy McVeigh. In 1990, Jared Taylor – a former Japanese language teacher at Harvard University - founded the New Century Foundation, an organization dedicated to supporting and defending racist views which he continued to propagate as editor of the magazine American Renaissance. In these roles, Taylor advocated for a form of racial/biological determinism, in which racism stems from “… an instinctive preference for their [one’s] own people…. And that they should prosper”, which as a biological mechanism is “healthy” and desirous. Taylor labels his views as race realism, hearkening back to arguments often utilized from the 20th century among eugenicists and – notably – the Nazis. Taylor emphasizes the right for “whites to love, first and foremost, the infinite riches created by European man”. Taylor’s views can be found echoing within the Young Americans for Freedom, VDARE, Identity Evropa, the British National Party, the French National Front, and the Council for Conservative Citizens.

Surprising to some, these ideas were, until recently, found even among mainstream news networks – notably MSNBC, bastion of left-leaning politics. Pat Buchanan, a former news host, was often interviewed by Rachel Maddow and aired his own news segment on the channel, in which he espoused proto-white nationalist rhetoric in an attempt to covertly drive the ideology forward. In 2010, he was interviewed on the radio show Cesspool, where he talked about the necessity of – demographically – increasing the birth rate of white Americans in order to combat the demographic shift; he further defended the logic of a gunman in El Paso, Texas, who walked into a Walmart in 2019 who murdered 29 people at gunpoint, believing he was defending America against an “invasion” from South America as “an accurate and valid description”. On the 2011 mass shooting in Norway, where a gunman murdered 77 university students after isolating them on a small island, Buchanan stated the racism of the killer was “right”. Buchanan later went on to write the book (which is cited in neo-Nazi, white nationalist, and alt-right circles as a central text) Death of the West, where he continues to defend racially inflammatory rhetoric in support of white nationalism. Buchanan is affiliated with the Sinclair broadcast group, of which Fox News is an affiliate.

White nationalism is far from only an American issue. Stephan Molyneaux, perhaps one of the most noxious contemporary advocates of the movement, can be found espousing his beliefs in social determinism, race superiority, and other pseudo-science errata on his radio broadcast in Canada; he advocates for many of the same ideas and beliefs found in previous paragraphs in his admittedly prolific, multi-thousand podcast series. Molyneaux is a vocal and ardent backer of nationalist politicians Donald Trump, Geert Wilders, Marine LePen, and of the author Murray Rothbard (coiner of the phrase “anarcho-capitalism” and a bell-curve racist); he also supports and props up the beliefs of David Duke, former Grand Wizard of the Ku Klux Klan. Far from stopping there, Molyneaux and his wife, Christina Papadopoulous (a disgraced psychotherapist found guilty of professional misconduct by Canadian psychiatrists) run a cultish, pseudo-therapeutic program for young, white men in which one of the prime directives requires the initiate to totally abandon and renounce the support of their families – a service which, surprisingly, generates alongside donations a substantial amount of money.

Individuals like Molyneaux, Buchanan, and Taylor, who, for many, are written off as the extreme racists they are, still find purchase among the right crowd.

In 2012, Adam Lanza – a high-school dropout, suffering from mental health crises stemming from severe social isolation and Aspberger’s syndrome, murdered his mother by shooting her four times in the head with a Bushmaster rifle; he then took her car to his old elementary school, Sandy Hook, walked in the front door, and murdered 20 children, 5 teachers and staff, and, ultimately, himself. Lanza spent days holed up in his room, active on online messaging groups and forums, with little meaningful connection to his father (whose account of his son is truly, in every sense of the word, heartrending) and arguably enabled by a permissive mother. On a damaged hard drive found in Lanza’s room, police found an immaculately organized spreadsheet documenting over 500 mass shooting events, the weapons utilized, and analyses of their efficacy. Lanza was 20 years old. The description of Lanza, given by his father after the events of Sandy Hook, is horrific.

In 2014, Elliot Rodger, a 22 year-old college dropout coping with Autism published a video outlining his manifesto, involvement and membership within the incel community, and advocating for a world in which women were exterminated in concentration camps. Rodger was a known user and contributor on PuaHate where he posted racist and misogynistic screeds, including a detailed account of an event in 2013 in which he was beaten severely by men after attempting to push women off a ledge. He later went on to stab three men to death after luring them into his apartment, then rampaging through Isla Vistaon a shooting spree against a sorority, where he killed three more and injured 14. He was chased down and shot by police.

In 2015, Dylan Roof, 21 years old, who was inspired by the writings of Jared Taylor and the Council for Conservative Citizens, walked into Charleston Methodist church on June 17 in South Carolina with multiple weapons, opening fire. He was regularly active and involved on the website The Daily Stormer. He killed nine people and injured one. Roof, a high-school dropout who suffered from opiod abuse and obsessive compulsive disorder, was a regular contributor on alt-right websites, where he was radicalized and motivated by posts describing massive and increasingly more prevalent incidents on black-on-white crime.

The call to violence is often, but not necessarily, isolated to young, white men. In 2017, former congressional candidate Robert Doggart was convicted on charges of soliciting others to commit arson (and, likely, murder) against a mosque in Islamburg, New York – a frequent target of white nationalist hate groups. Doggart, affiliated with white nationalist militias, advocated for individuals willing to comply to bomb the mosque with molotov cocktails and attack the building with firearms and machetes. Regarding the attack, he stated that he “[did not] want to kill children, but there’s always collateral damage”. He was led to believe by alt-right literature to believe that residents and patrons of the mosque had a plan to commit violent acts against American citizens, and believed that it was his duty to marshal like-minded individuals to, if necessary, conduct a preemptive attack on the mosque. Doggart was diagnosed with narcissistic personality disorder, bipolar disorder, and had his sentence appealed to 5 years after a technicality in his trial led to a judge shortening his sentence from 20 years.

In 2018, Robert Bowers, a user of alt-right messaging platform GAB and known supporter of the Proud Boys, Jim Quinn, Patrik Little, Brad Griffin, and the League of the South, walked into the Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburg, PA where he murdered 11 and injured 6. He was radicalized after numerous discussions and conversations with alt-right members such as the anti-Semite Jared Wyand. Before entering the synagogue, Bowers posted online, describing the Jewish community as “invaders”, and his last online communication, posted after a discussion regarding whether the alt-right should work harder to veil their anti-Semitic, white supremacist message said: “screw your optics, I’m going in”.

The efficacy of online, extant alt-right groups must not be understated: supposedly lone-wolf actors in American shootings are radicalized, involved in, and are supported by openly or clandestinely-run organizations. An organization called The Base (which, hilariously, is the English translation of Al-Qaeda), founded by Rinaldo Nazarro and the White NWF/NVA (white nationalist militias in the Pacific north-west), espouses the ideologies of the white ethnostate and christian identity movements spread by Richard Girnt Butler – founder of the Aryan Nations. Nazarro, a former member of the United States armed forces, called for “revolutionary struggle”, “lone-wolf operations”, and guerrilla warfare as a “propaganda of the deed” in 2017 after a stint in prison and an encounter with James Mason’s book Siege. A known associate of Atomwaffen, Wire, Fascist Forge, SWAN, The Lads, Antipodean Resistance (who ran a racist, anti-black/muslim protest in 2019), The Base sought to recruit Brenton Harrison Tarrant into their organization, and attempted to distance themselves from him after the events at Christchurch, New Zealand, where Tarrant, a 28 year-old white male and frequent user of 4Chan livestreamed himself walking into two mosques with semi-auto shotguns and assault rifles, murdering 51 people.

Tarrant was an active supporter of the IBÖ, an Austrian branch of Generation Identity, and of Blair Cottrell and fascism. Tarrant posted a manifesto littered with neo-nazi symbology, and styled himself as an etho-nationalist. Notably, the “14 words”, a phrase coined by white nationalist David Lane and used by many involved in the Proud Boys and Identity Evropa to denote membership in white nationalist circles, were inscribed on his rifle.

On August 25, 2020, a 17 year-old Illinois native drove across state lines with an assault rifle to Kenosha, Wisconsin, with stated purpose of defending the property of a car dealership that had experienced property damage in relation to the massive protest of the police shooting of Jacob Blake two days prior. Rittenhouse, a minor, illegally transported the weapons across state lines, and was later recorded shooting three protestors in an altercation on the streets of the city; two of those protestors died, and a third was injured. Rittenhouse then walked away from the scene of the crime, hands in the air and rifle slung across his chest, as a multitude of police officers drove right past him towards the scene of the crime, even as protestors who witnessed the scene actively informed the officers that Rittenhouse was the shooter.

Rittenhouse returned home, and later turned himself in to authorities on August 26th in Illinois.

For a case study in Colorado, look no further than Identity Evropa, founded by Nathan Domingo and Patrick Casey who describe themselves as “identitarians” (read: white nationalists) who believe in raising and uplifting white, western culture. Identity Evropa is primarily focused on actively spreading propaganda on college campuses, where they have been known in 2019 to post posters, organize rallies, and create local chapters among 13 college campuses from Fort Collins to Pueblo. Identity Evropa was directly involved in the planning and execution of the Unite the Right rally, and are known supporters of David Duke, J. Phillipe Rushton, Nicholas Wade, John Bolear, the National Youth Front, and the ideology of ethnopluralism (a veiled belief that espouses the importance and establishment of distinct ethostates, in an attempt to legitimize white nationalism). Organizations like that of Domingo and Casey skirt the outermost edges of civil discourse, relying upon patently bad-faith usage of free speech in order to discreetly advance racist, xenophobic, and violent ideologies to young men.

Organization, Structure, and Dynamics of Potentially Violent White Nationalist Hate Groups

The Department of Homeland Security, in their prescient 2011 publication Organizational Dynamics of far-Right Hate Groups details a number of factors, gleaned from an analysis of many extant publications and databases of hate crimes, violent actions, protests, and events gathered by state law enforcement agencies and hate group watchdogs such as Klanwatch and the Southern Poverty Law Center. Federal organizations have often recognized the serious threat that white extremist organizations pose in the United States since the 1990’s, especially after the events of Waco, Ruby Ridge, and the Oklahoma City Bombing; this recognizance, however, in the public domain remained a topic of fringe discussion until the unfortunate events of the last decade. In this report, the DHS gathered data regarding known hate groups that have remained extant for at least three years. The DHS noted the rarity of an organization remaining active past one year, citing the challenges (not surprisingly) all political organizations face: membership, funding, and involvement by its actors in promoting/propagating the group. The DHS was largely motivated by its discovery of a lack of quantitative research in the subject, even after markedly violent, disturbing events with hate groups in the 1990’s. It is widely reported in this study that, among state law enforcement offices, far-right hate groups represent the gravest concern regarding terrorism within the United States.

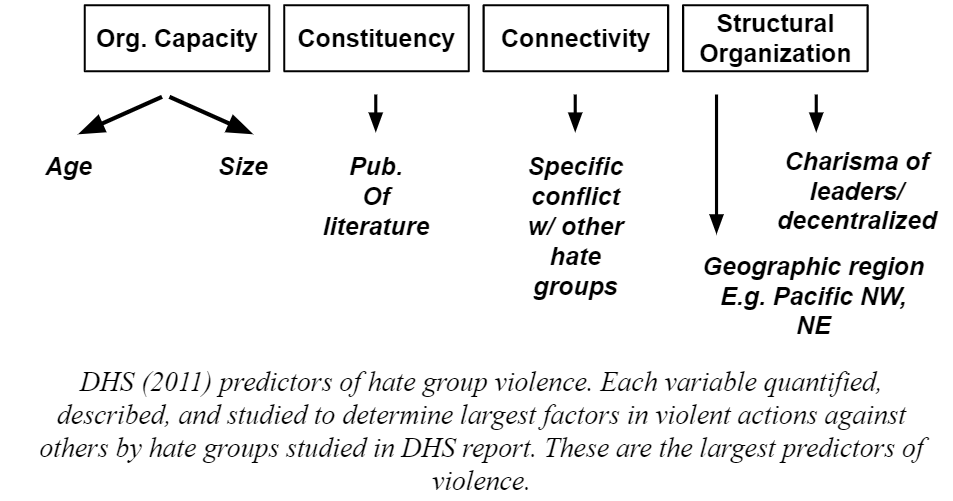

After conducting a survey following these criteria, the DHS compiled a database of 275 far-right groups, responsible for killing 560 people between 1990 and 2010. Of these organizations, the report classifies them as “violent” or “extremely violent”, depending on the number or magnitude of instances in which the group was active in violence against others. The DHS classifies organizations on multiple statistical variables, detailed in the diagram below.

Figure 3: DHS (2011) predictors of violence among far-right hate groups

The variables most strongly correlated to a group’s propensity for violence are described in figure 3. A description of these variables is necessary, though, to fully appreciate the DHS’s findings.

Organizational Capacity describes a hate group’s ability to recruit new members, notably former military members, as well as the group’s age, overall size, and the state of its funding. The DHS found that, while indeed true that far-right hate groups target and recruit former military/police members, this recruitment was not as strongly correlated to the group’s odds of engaging in violence as the age of the group itself and its overall size. Furthermore, funding itself was not necessarily a predictor of violence: particularly well funded groups, it seems, are more likely to be old or have a greater number of members, and these predictors were more powerful in terms of predicting violence. Notably, groups that were present at protests for far-right causes were more likely to recruit and engage members in violent actions: having “skin in the game”, it seems, was a predictor of someone’s ability or willingness to physically act out versus someone recruited online.

Organizational Constituency describes a group’s propensity for attempting to legitimize their beliefs through literature and media among the public, through political involvement, publication of literature, involvement on the web, organized conferences, etc. The vast majority of hate groups were active in disseminating at least one of these strategies. Of the previous, the involvement in publication of hate literature was the most closely correlated to involvement in violence; in an interesting twist, however, the group itself publishing the literature was not likely to incite/commit a violent crime. Hate groups closely linked to publishers, instead, were the ones likely to perpetrate a crime, in a variable described by connectivity. It is the DHS’s thinking that groups more active in publishing hate literature have already drawn enough attention to themselves, and instead are more focused on legitimizing the discourse surrounding their ideology rather than the execution of their beliefs; this, the DHS believes, is best left to other organizations tied to the publisher.

It is here that I would like to note the connection of “literature” described by the DHS and the publication of “plausibly deniable” content on the internet. This description of propaganda, while given in very formal terms, can take an interesting turn when one considers the persuasive power of informal methods of disseminating ideas – YouTube videos, news segments, memes, and social media posts.

Connectivity describes a group’s propensity for connecting with and forming – oftentimes darkly competitive – relationships with other like-minded organizations. The DHS noted that groups with internecine conflicts (those who, surprisingly, disagree with rather than agree with) were more likely to be violent; this is perhaps seen as a way of attempting to legitimize one’s own organization over another. The connection between the violently competitive culture among these groups is particularly disturbing, and offers a fascinating window into predictions of violence by known groups moving forward.

Lastly, Structural Organization describes a group’s self-organization strategies as hierarchical, traditional groups or as decentralized, splinter “guerrilla warfare” groups. Of this category, groups with highly charismatic leaders were particularly likely to engage in violence, often incited by individuals who are particularly gifted in rhetoric and persuasion. Decentralized groups were (and, in light of modern events) particularly likely to be violent, and extremely so.

Each of these variables was useful and significant in the prediction of a group’s propensity for violence. The DHS, in studying these variables ten years ago, contributed to a sorely anemic field of literature surrounding organizations involved in hate crimes, violence, and disruption of civil function in society. Research into the field continues to lack serious, quantitative research; despite knowing that far-right groups are much more likely to be responsible for destructively engaging with American society and government, little in the way of research, funding, and understanding of the problem has been conducted in the last decade. A multitude of organizations – aside from the federal government – are involved in attempting to solve this problem, and they are often cited here in this essay.

The Terrible Cost of Anger – Radicalization

It goes without saying – or perhaps, unfortunately, with the necessity of saying – that the actions of Adam Lanza, Elliot Rodger, and Dylan Roof – among the many others responsible for the brutal murder of American citizens by association – that there is no forgivable justification here. The actions of these individuals, fueled by partisan, false, and horribly twisted rhetoric driven by baseless cowards are no less than a complete renunciation of the work our nation has done in the attempt to create a just society. If, in the case of Black Lives Matter protests turning violent, we are drawn to the conclusion that a government’s responsibility is to the protection of and provision of civil rights and law, and that such a government is obligated to the defense of those rights forcefully if necessary, it is unequivocally true that these hate groups represent something much darker and more sinister still. The equation of these two groups is an inherently flawed and particularly malignant attempt in delegitimizing the very real problem of inequality in the United States, the lawful action taken to address it, and the duty of the American citizen to address the issue responsibly as a member of that society. I will never give nor accept redress for the actions of the individuals I described above. They are nothing short of cowards, and in relation to them, the individuals driving such hateful ideologies are nothing more than bastards.

This particular segment of research was, to me, deeply unsettling. One of my first memories of moving to Colorado in 2012, was a discussion I had with two new classmates in high school about the Sandy Hook school shooting, gun rights, and politics. I had a cursory knowledge of the events, and, I think given my youth, I wasn’t able to fully appreciate the terrible reality of what had occurred. When I was gathering research on Adam Lanza – and the other mass murderers I compiled for this essay – I was often struck by an awful conclusion:

These were young, white men, disillusioned by the world around them, isolated and susceptible to malignant and hostile ideologies propagated by hateful individuals.

They, even though acting on a set of fundamentally different beliefs from myself, were as equally convinced of their standpoint as I am.

It wasn’t until halfway through reading the account of Adam Lanza’s father that I recognized how closely related these people were to myself, and to others that I know. Like many Americans, this year (let alone the last four years, reading news headlines on the web/the television about the state of our presidency) has been a particularly vexing and infuriating time. I’ve seen events in the news that I never would have envisioned happening in my own country. But, like myself, I implore you to look inward, and address something within yourself that I feel as well: the bitter, pessimistic anger. Anger is, like any other emotion secondary or primary, part of the human experience. Anger drives us to make change, to seek redress, and correct a problem. When improperly utilized, it is blindly destructive. Ideologues and extremists, if you don’t keep yourself in check, will try to manipulate you using your anger, your isolation, and your very human need for justification and belonging.

After reading about Lanza, I came very near to tears. Here, under the hateful ideology, the unforgivable crime, and the abysmal circumstances in which he came to his conclusion, I recognized within myself a not dissimilar anger and disappointment with the state of the world. Like Lanza, I, and all of us, are products of the ideas, beliefs, and statements we read, hear, and speak. It is easy to feel alone and isolated, especially when one views the world as incorrigible; without redress, or hope of the ability or avenue to enact change, extremism takes foot and foments.

In 2020, I know I’ve felt a huge array of emotion in my personal life, but also as I watch the events of the year unfold around me, whether it’s to do with the protests around racial inequality, the presidential election, or the topic of white nationalism. I’m angry. And in that anger, it’s become increasingly easy for me to refuse to listen to anything other than the narrow set of beliefs, the few sources of my information, and the communities I surround myself with. It’s become even easier to legitimize, if only through hyperbolic repetition, extreme statements and stances in response to perceived or actual injustice.

You cannot let yourself succumb to this.

This is not a unique feeling: people of all races, creeds, and beliefs have come into a world of late in which particular ideologies propagate through media that is constantly and intrinsically connected to the way we view the world and, more importantly, how we view each other. It has never been easier than today to demonize the other and justify one’s own beliefs, no matter how wrong or harmful they are to others, particularly if those beliefs give us a sense of community and belonging. This has been the great draw of extremism throughout history and throughout the world: the promise of a community, purpose, and vindication. Watch for the sleight of hand – it’s subtle, but it’s there, I assure you.

When I listened to Trevor Noah ask the question “why don’t black people loot Target?”, my first instinct was to agree: why the fuck not? It’s taken months of research, thinking, discussion, and consideration of ideas, arguments, and information outside of the narrow confines of what the news, the internet, or like-minded individuals have told me to finally come to the realization I’ve argued here. It took even longer for me to recognize that, while not in the same vein as those in the alt-right, I was just as radicalized in my beliefs as they were – and not even for good reasons. It’s hard goddamned work. But in exercising your faculty for considering an argument, for engaging in discourse with others, and for engaging in the society you benefit from and exist within, I hope you’ll come to the realization about a few inalienable facts. I know you’ll become a better person for it.

In taking a moment to stop and question my beliefs, I learned a few things about the world, and about myself. It’s a lesson in civics I never expected to learn – and, I hope, never to have to learn again.